Chapter Six

Hendricks Field After the War

In retrospect, it seems that the entire City of

Now, (January 1946) that was past. The war was over. The boys were not being shot at so they were

being dismissed from the service and were coming home. Rationing was not being enforced and business

was coming back to normal. Reaction had

set in so the movement was to get as far as possible since all the military and

most of the nonmilitary personnel had left, leaving a feeling of great peace

and quiet.

As a result, there was widespread skepticism among the

citizens of Sebring, as to the wisdom of

the City accepting the cancellation of the lease of Hendricks Field and the

acquisition of some of the buildings and facilities on the property. Only a few members of the Chamber of Commerce

and the City Administration had any vision of the potentials offered by

accepting responsibility for the maintenance of the property.

The City Council was caught in the middle of the

arguments. They were pressured by some

to accept the facilities as the foundation for expanding opportunities for

manufacturing, new industries and trade potentials. Here were good, solid buildings just waiting

for tenants and many of the service men returning home with visions of going

into business for themselves needed the building space that would be

available. And, by installing business

in the area, jobs would be provided for returning veterans. Space for such commercial expansion was not

available in the area except at the abandoned airport.

At the same time, the aviation facilities would eliminate

any demands for financial outlay for decades in the future, for airport needs

and aviation was certain to become an important part of the future American way

of life.

On the other hand, a popular notion was that “it would take

no less than $50,000 a year to maintain the property and the City could not

afford to include that amount in the budget.

The City had made its profit on the investment and should turn the land

back into a cow pasture.” There were

only a half dozen small planes in the community and the little sod field on the

west side of the lake would accommodate them and the foreseeable increase. These arguments were offered by several

well-respected citizens.

How could the City Council please both groups? Both sides had valid arguments and included

levelheaded and respected businessmen and taxpayers. And both sides were very vocal in expressing

their opinions; a few in favor and many opposed.

It so happened that the choice came before an

administration that could not be stampeded into ANY position either for or

against and hence, finally offered a decision that the City would accept the

property if the proponents would agree to guarantee that the City would be

responsible for no expense above the proceeds that could be generated by the

airport property.

The Administration also struck a favorable bargain with the

War Assets Administration that was eager to get the property off its

hands. By agreement, the City was given

(without cost) all the buildings and equipment necessary to operate an airport

(including water works, sewers, etc.), but bay warehouses or similar

structures, not essential to an airport, would be available only by purchase at

very reasonable figures. And the City

was to be high on any priority list in the choice of buildings.

With the City Administration, the Chamber of Commerce and

the objectors all in agreement, the prospects of success seemed rosy until the

actual mechanics of putting the agreement into operation began.

The Chamber of Commerce had applications for space with

firms that wanted to get into business but the wheels of government turned

very, very slowly. A “caretaker crew” of

the War Assets Administration took over.

It was the duty of this crew to dispose of everything that was not

conveyed to the City, and they did a definitely thorough job of it. There were dozens of buildings with

furnishings such as: fans, lighting fixtures, boilers, refrigerators, motors,

and every other removable item... even down to the fuses in the switch boxes,

disposed of. In fact, such a thorough

job was done that it included everything that could be clandestinely removed

from the buildings to be conveyed to the City.

Although the City was given a “right of entry,” there was

no way in which any funds could be made available for months and yet, the City

was at some expense in merely protecting what would later become city

property. The War Assets Administration

was selling many buildings and private contractors were removing them and, at

the same time, removing anything else they could get away with. But the “right of entry” did not permit the

City to occupy or rent out any of the buildings. This condition existed for almost a year and,

as there was no income but some expense, the funds came from the pocket of the

manager. Before the City enjoyed any

income, the figure had reached $1,500 which was never recovered.

At last, it was learned that a warehouse could be made

available to be rented to a man who was clamoring for space. A building of 9,000 square feet, on the

railroad siding seemed ideal for his distribution business (beer). The government was asked to set a rental

figure for a period pending transfer of the building to the City. They stipulated “the going rate in the area.” Three local realtors agreed that one cent a

square foot per month would be fair to all, to which the client agreed. But, when payment was made to the government,

they insisted that the City should furnish adequate fire, storm and liability

insurance, as well as some assurance of police protection. The client did not agree to an increase to

cover the additional costs.

The Eighth Air Depot, Inc., inspected the field and found

exactly what they needed to inaugurate an aviation-related business that would

use buildings to which the City had been given title but the government chose

these buildings in which to transact their business because they could hold

these places as long as they were needed, whereas the others were subject to

sale at which times their operations would be forced to move out.

This maneuvering continued for so many months that it

appeared that the government was doing everything to delay transfer and, had

there been some graceful way to “throw in the towel,” those who had made such

rosy predictions would have gladly conceded defeat. But, several prospective tenants had been

assured of locations, so the only thing to do was to continue to struggle.

And even before the government withdrew, the struggle

became more bitter. At the time the

facilities were built, some materials were in short supply and certain

substitutions had to be made, which could only be considered as temporary, so

some malfunctions began even before the government “caretaking crew” was

withdrawn. But the repairs that this

crew made were makeshift or “bandaids.”

Some failures were not even given attention. One such condition was the failure of roofing

materials. Literally acres of roll

roofing of a rather unique specification had been used. Instead of a half-lap over flint coated

material, the half that was covered did not have a flint coating. As result, after a few years in the hot

Another and more pestiferous failure occurred in the water

lines. The mains were of asbestos pipe

with cast iron fittings. The joints in

the pipe were sealed with rubber rings which remained satisfactory as long as

they remained wet, but where the pipes joined the fittings - these were

caulked. At the time the system was

installed, lead for the caulking was almost impossible to find. (This may have been caused by the tremendous

demand for lead at the

A substitute, known as “leadite,”

was used. This was a brittle substance

that would tend to flake off. A pinpoint

leak would develop and the swirling action with the surrounding sand would cut

a bigger hole in the pipe. The cure was

to dig out the leadite and replace it with lead and

to repair the hole in the pipe. There

are hundreds of these joints on the property and, in the first ten years of the

City occupancy, probably 95% of all the joints were replaced with lead. It became the standard practice to re-caulk

with lead, all the joints in a group, when the hole was open to repair a leak.

One such leak presented a problem worthy of special

note. This occurred in the middle of the

street adjacent to the base of the water tower.

Nothing in the blueprints showed how far below the surface the pipe was

located but after digging for three feet with no pipe in sight, it became

evident that it was necessary to “sheet” the hole because the water table was

high and the sides of the hole began caving in like so much granulated

sugar. When the hole was five feet down,

the sheathing had to be moved out to accommodate a hole ten feet square. (see photos)

The ground water level was so high that two dewatering

pumps were kept working continuously.

The pipe (16 inches in diameter) was found at something like six or

seven feet and the repairs started.

Since this was the only connection to the elevated reservoir and since

it was necessary to valve off the tank, the pumps from the wells had to be kept

running 24 hours a day to supply water to the entire field. And work on the repairs was carried on for

nearly two weeks, day and night. Had it

not been for the high ground water level, this would have been a routine job

but, as it was, it was like working in a swimming pool, underwater. And the job couldn’t wait for the water to

recede.

Repairing leaks in the water lines.

One favorable condition resulted from the delays in the

transfer of responsibilities to the City.

A backlog of applications for space indicated a demand which justified

the Council to advance approximately $22,000 to finance the purchase of

buildings and the railroad siding. No

definite articles of agreement were arranged at that time nor had any of the

fiscal understandings been reduced to writing.

These conditions posed no immediate problems but as the personnel of the

Council changed, so did the relations between the Administration and the

airport.

As had been anticipated, many returning veterans had had

visions of starting their own enterprises.

Some, with savings made while in the armed forces, invested them in

stock and equipment but found that the expected markets were just not

materializing, so the majority of the hopefuls lasted only a few months and

then gave up the race. The turnover of

renters on the field was rather great in the early years.

One group found the location they considered ideal for

their venture. They named their new

company “Veterans Air Lines,” which was descriptive of its components. It was composed of ex-servicemen who had a

dream of an airline in which all employees owned stock and each employee earned

the same salary as every other employee, be he “grease monkey” or the general

manager.

As they were all veterans, they found that they had

priorities that were not enjoyed by ordinary entrepreneurs. They were in line for priorities in the

purchase of Government surplus planes, parts, equipment and materials as well

as having special privileges in government contracts. So, from the very beginning, their success

seemed assured.

When they came to Sebring, they had acquired a couple DC-3

planes (the most efficient, at that time, for their purposes). They had managed to obtain several very

lucrative cargo contracts and were readying two more planes for cargo

service. It seemed that they would soon

require more space than the one large hangar that they had rented and that they

would need more men on their maintenance crew.

They paid their bills promptly and built a good reputation in all

ways. But, without prior indication,

they announced that they were reorganizing their business structure and were

moving from Sebring. (No definite

information was ever obtained but, from hints obtained from the principals, the

impression was gained that the business had been so successful that the owners

of stock in the corporation could not refuse the very profitable offers of

merger with another airline in another location.)

If any one group can be given credit for the continued

existence of the Sebring Air Terminal it would be, without question, the Eighth

Air Depot, Inc. In brief, this company

can be described as an organization of three young men who had been associated

in World War II and who, in their leisure moments in camp, planned a

corporation to repair large cargo and passenger planes and engines. Their names should be definitely and

permanently associated with the airport. For without them, in the beginning,

the project would have failed and all the buildings and facilities would have

been moved because there were other cities and airports who were clamoring for

such things as hangars, water and sewer facilities and other equipment which

Sebring acquired. These three men were

Art Dorman, George Dumont and Bob Kiel.

The story of their association and of the Eighth Air Depot, Inc., is

worthy of a complete chapter of its own.

Turning the property over to the City involved at least

four bureaus of the government - the Army Corps of Engineers, the War Assets

Administration (WAA), the Federal Aviation Authority (FAA), and the Housing

Authority. With the exception of the

Engineers, these bureaus were all new agencies and it appeared that they made

the rules of the game as it progressed.

Of course, the City was new at the game, too, but it had a champion in

its corner, who was a wizard at getting answers to problems - Congressman J.

Hardin Peterson. When the Housing

Authority proposed to remove all the civilian housing units which the City felt

it could use, a call to the congressman settled the question, quickly.

It is almost unbelievable how many different complexities

could develop unless it is considered that each of the agencies had their

positions to defend, and that there were large numbers of properties in the

state undergoing the same procedures as was Hendricks Field... and all this by

what might be considered amateurs in a professional field. The City had a disadvantage in that it was

low in the list having priorities. The

State, the schools and other government agencies all had preferential

positions. Items of property and

equipment which were not specifically set up on the transfer papers, could be

requisitioned by those agencies having priority and requisitions of the City

were eliminated. One item of this nature

(by way of illustration) was the bucket of a dragline. The dragline was specified as being essential

for the maintenance of the field but the bucket, which supposedly was a part of

the machine, was not mentioned so when a state agency asked for the bucket, it

was awarded to them even though the machine could not be considered as a

dragline without a bucket.

The War Assets Administration sold surplus pipe that was dug up adjacent to runways… leaving a mess for the airport administration to fill.

A somewhat similar case was narrowly averted by an

accident. The air traffic control tower

was not one of the specified structures but it was considered as essential to

the operation of an airport, especially inasmuch as all of the equipment in the

tower was on the personal property list.

Several months went by after agreements had been reached, without any

reference to the tower so it was assumed that it was City property. One Friday afternoon, a plane left

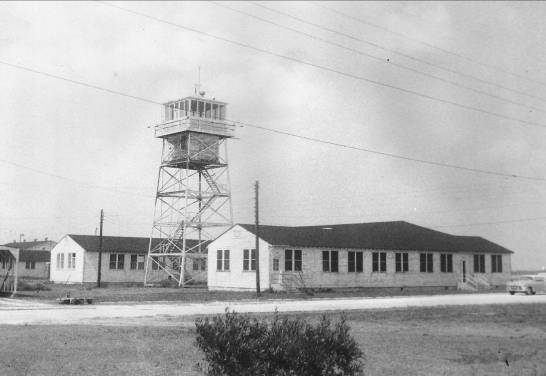

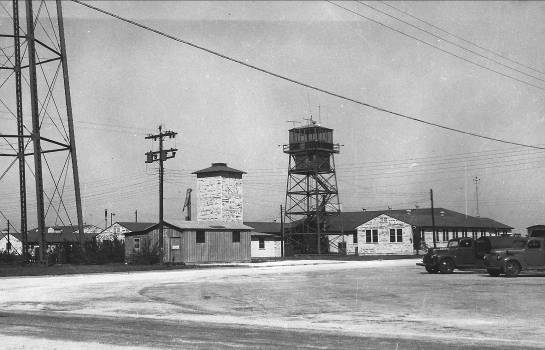

Headquarters building & control tower, ca. 1955

It seemed that the first couple of years were spent in

fighting to keep possession of the properties the City thought it had been

granted. While it was successful in some

cases, many skirmishes were lost - machine tools, emergency power plant,

trucks, and other equipment went to others.

The inexperience of the City in negotiations of this nature cannot be

overemphasized. Starting with the origin

of the installation, the City found itself in an area with which it had no

previous experience. It must be

remembered that 1941 was a year of intense emotions as everyone knew we were

standing on the brink of war and everyone was willing to agree to anything that

would favor the position of the

The stipulations had no effect on the operation and

management after the City took over, but one other innocent-appearing clause

did have a devastating effect. This was

known as the “recapture clause” and for twenty years was the major impediment

to progress on the field.

The City had title to the land and negotiated a lease to

the government for the consideration of a dollar a year with no definitely

specified number of years. In the

cancellation of the lease was a clause that, in the event of a national

emergency, the government could reoccupy the property under the previous

conditions. No provision was made for

reimbursing any tenants on the property for any damages resulting from their

ouster. For “nickel-and-dime”

businesses, this offered little threat, but for a firm with any considerable

investment, the hazard made location on the Air Terminal out of the question. Many promising prospects were turned away by

this clause.

As an alternative to this problem, there appeared to be

possibilities that the area could become a government installation - first for

a bomber base, then for a helicopter training base and for other unspecified

uses. It was understood that the

competition for the bomber base laid between

The funds that were advanced for the purchase of the

warehouses, the railroad siding and other facilities, came from the proceeds of

the sale of several blocks of airport land on the outskirts of the field and,

although these sales returned several times the investment, it was agreed that

there were some materials which were not essential to the airport but which

could be used by the City to advantage.

One example of this was the clay in the “hardstands” which the Army had

built on which to park the giant bombers.

The City could use this clay for paving alleys and secondary streets in

town and the airport had the equipment for loading, spreading and leveling the

materials. So this was one other method

of repaying the advanced funds.

But the implementing of this policy established a new

relationship between the administration of the City and the airport. The view became general that, as the airport

belonged to the City, so also were the components of the airport, the property

of the City. After a few years, it

became common practice for the various departments of the City to “requisition”

equipment and material without regard to the needs of the airport - the

utilities, at times, needed transformers; the sanitary department “borrowed”

the bulldozer and road grader for several years; the former for continuous use

at the City dump and the latter for general maintenance. These and other airport assets came to be

considered as general city property to be used without credit to the airport,

but they were always returned to the airport when repairs were needed to keep

them in operation (the repairs to be made at the airports expense).

One policy, however, was remembered and strictly adhered to

- NO CITY FUNDS WERE EVER USED TO MAINTAIN AND/OR OPERATE THE AIRPORT OR ITS

PROPERTIES.

There was really no tangible basis for the estimated

$50,000 annual maintenance cost and it was found that, had the funds been

available, twice that amount could have been spent wisely or, as was the case

in the first few years, half that figure would keep the area in operation but

would not keep pace with depreciation.

Experience was a good teacher. On

one occasion, Sebring was on the outside edge of a hurricane which played havoc

with some of the roofs of the warehouses at the very time when there were no

reserve funds. By juggling credit, the

crisis was met and a policy was adopted at that time. Each month, a portion of the income would be

set aside in an emergency fund. No

matter how hard pressed, SOME money went into this fund.

At the same time, it was decided to make repairs at every

possible point where it could be done in the most permanent manner. The idea of replacing roll roofing was

discarded and in its place, metal roofing was substituted. As buildings having wooden siding would

require repainting, it was estimated that there was such a great area that a

painting crew would never finish so, as rapidly as possible, asbestos siding

which required no painting, replaced the wood.

At the period when the City acquired the buildings, it was already passed

the time when repainting should have been started and many were in need of roof

repairs, but gradually progress began to become evident.

The emergency fund, which was so painfully accumulated,

also began to show some promise but, by this time, the membership of the City

Administration had almost completely changed and the original understandings

were fading, if not entirely forgotten.

At one council meeting, the chairman of the City committee, suggested

that the airport emergency funds be used on a city project. The following day, some airport projects

which had been put on “the back burner,” were given immediate action. This move did not improve relations between

the two administrations - neither did it damage them - it merely brought them

to the surface.

A majority of the City Administration sough to find points

where criticism could be leveled at the operation of the airport and it seemed

that no operational policy could meet with council approval. An example of this attitude appeared when one

councilman expressed his opinion that any prospective executive would be

discouraged if he discussed bringing his business to the Air Terminal in

offices that had never been made attractive but were as bare and dreary as they

had been ten or twelve years previously when they were first acquired. So, to counter this criticism, the offices

were “dolled up” and given a modern appearance.

This drew a response from another councilman, in open meeting, that “the

money spent to beautify the offices could better be used to upgrade other

facilities on the property.”

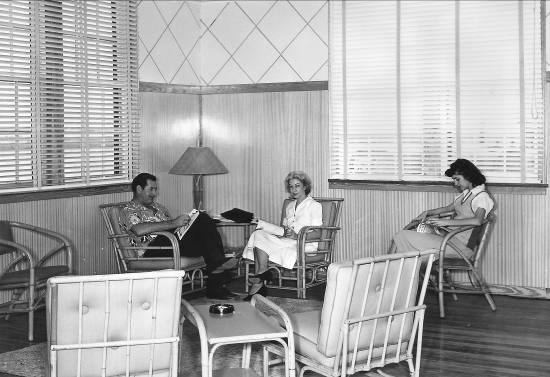

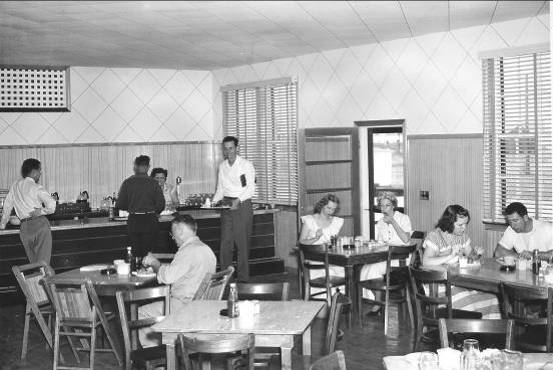

Office in headquarters building, refinished by the City.

Except for the influences of the Eighth Air Depot, Inc., it

is questionable if the Air Terminal would ever have gotten off the ground. This was not only the first firm on the field

but it was also the most reliable. In

every instance, their check was in the mail on time while in many other cases,

much time and pressure were expended to collect past due accounts. The “Eighth” also brought other accounts to

the Air Terminal. They bid on a

government contract and were awarded a project that required a couple hundred

mechanics and a great deal of material to overhaul the planes in the

contract. Their search for replacement

parts revealed a possibility of a profitable dealing in materials available in

government surplus channels. To engage

in this venture, they brought in two firms (the Miami Aircraft Supply Co., and

the American Industrial Sales Corp.).

These firms soon found heavy financial backing and began to bring in railroad

boxcar loads of all manner of industrial materials. So great was the volume that they rented

seventeen buildings at one time and had large quantities on the grounds outside

the buildings, waiting for space and cataloging.

The action of moving these stores into buildings caused the

Air Terminal quite some grief. While the

original design of the warehouses provided for protection against termites, it

could not prevent them from being carried into the buildings when the materials

were taken in after having been exposed for some weeks. This lesson learned was very expensive.

In the negotiations of the provisions of the cancellation

of the lease with the government in 1946, the “recapture clause” seemed

innocent enough and was not viewed as a negative factor in the establishment of

commercial enterprises on the airport property.

In conversations with prospective tenants however, it was found to be

the greatest stumbling block in the struggle to entice substantial firms to

consider the Air Terminal as a base for their organization.

The government was adamant in its refusal to eliminate this

clause and, at the same time, it continued to send parties to inspect the

property with respect to its possible use as a point of military operations, in

whole or in part. Such parties attracted

much notice in the news media and this had a negative effect as did the fact

that the frustration that the publicity generated inspired the Sebring public

to court government occupancy as an answer to the problem of obtaining reliable

and continuing users of the facilities.

Several prospective tenants found difficulty in obtaining

adequate financial backing for ventures that gave promise of stability because

of these restrictions and so, the Air Terminal, in its efforts to acquire

tenants, had to resort to rates below value in some cases and in others, it was

found that as costs of labor and materials advanced, rental rates could not be

increased to meet conditions.

Many factors contributed to the difficulties of the Sebring Air Terminal in adequately maintaining the buildings and facilities in the first ten years of operation by the City, but the greatest impairment was the “recapture clause.” It can be imagined why the government was hesitant to remove restrictions while the nation was in a “state of emergency” because of the Korean conflict. One inspection after another kept the issue in the headlines and depressed the market for the facilities offered by the airport.

In the late 1950’s, the fortunes of the airport took a

turn for the better. The sequence of

events was, in general, as follows:

1) The State signed a contract for the use

of several buildings at prices and conditions favorable to the City. This permitted the airport to borrow money to

improve facilities and increase rental rates as well as to improve cash flow.

2) The City administration entered into the

action by modifying its position and advancing monies for operation.

3) The government modified its position on

the “recapture clause.” The threat of

war in the Korean area abated and the constant flow of inspections and rumors

of government use subsided.

4) Several different offers were made to

take over the field by private interests who would pay the City a royalty for

the privileges. This stirred up

controversy and public interest.

5) Nationwide, money seemed to be more

readily available, and locally it appeared that business had settled down and

the businesses which had been established on an experimental basis had either

failed and vanished or had succeeded and become stable.

6) The Council appointed an “Airport

Advisory Committee” consisting of five “blue ribbon” civic leaders, then the

Council proceeded to make important actions, hold meetings with prospects, and

to make deals, all with relation to the airport but without any reference or

consultation with the members of the Advisory Committee and on some matters,

the Council acted contrary to the advice of the Committee. So, the Committee resigned en masse, in

protest.

7) The Council replaced all the airport

personnel and sold many of the ancillary assets (power lines and franchise,

machine tools, certain buildings, etc.) to obtain funds to upgrade maintenance.

8) By this time, the attitude of the City

Council had changed 180 degrees.

Originally, the Council had adopted a “hands off” policy placing the

entire responsibility on the appointed airport personnel with no city money

involved. By 1960, the policy changed;

the airport management could not make even the least important decision without

Council approval, and the restrictions which limited the operational costs to

airport income were removed.

9) Almost suddenly, it appeared that

EVERYONE in town became intensely interested.

By almost universal demand, and act was passed by the legislature

creating an “airport authority.” This

removed all responsibility for maintenance and/or policy making from the City

Council and vested it in the “Airport Authority.”

The first

fifteen years or so in the life of the Sebring Air Terminal, were stormy. The first part of this era was very difficult

because there was practically no interest or cooperation on the part of the

local citizens and very little by the Council.

They seemed to want no part of the project.

The next period

suffered because the elected administration wanted absolute authority but was

not sufficiently informed to act wisely.

The legislation creating the Airport Authority and separating the

operation from the City Administration, together with the elimination of the

recapture clause, changed everything and the airport entered into an entirely

new chapter in its life.

Individuals who purchased buildings for off-site use, for the most part, complied with the provisions of their contracts which required them to clean up the debris…

but in many instances, where the costs of such cleanup were greater than the $50 performance bond, they elected to forfeit the bond and leave the trash.

Even where a cleanup was performed satisfactory to the WAA, hundreds of hours of work remained in removing concrete piers and debris

which made the property unsightly and made mowing and other work impossible.