Allen Altvater

Main menu

- Home Page

-

Allen C. Altvater

- Allen C. Altvater

- Circle Theater

- Papa's Multigraph

- Family Photo Gallery

- 73rd USN Seabees - WW II

-

Altvater Genealogy

- Altvater Genealogy

- Parents of Allen Sr.

- Grandparents of Allen Sr.

- Kretschman Genealogy

- Warvel Genealogy

- Estes Genealogy

- Price Genealogy

- Moyer Genealogy

- Ingle Genealogy

- Allen C. Altvater, Jr.

- About Being Fired

- My Resume'

- Life Accomplishments

-

Altvater Library

- Sebring Fire Department

- Civilian Conservation Corp

- Highlands Hammock

-

Sebring Air Terminal

- Sebring Air Terminal

- About the Author

- Foreword

- Chapter 1 - The Origin of Hendricks Field

- Chapter 2 - No Army Camp for Sebring

- Chapter 3 - Early History of Hendricks Field

- Chapter 4 - Hendricks Field 1941-1945

- Chapter 5 - Hendricks Field

- Chapter 6 - Hendricks Field After the War

- Chapter 7 - The Eighth Air Depot, Inc.

- Chapter 8 - Ghosts of WW II Planes Still Roar

- Chapter 9 - Congressman J. Hardin Peterson

- Chapter 10 - Historical Documents, Letters, Telegrams, etc.

- Chapter 11 - The Race

- Chapter 12 - The Races

- Chapter 13 - Reports and Memorandums

- Chapter 14 - 12 Hour Grand Prix

- Maps

- Additional Documents

- SAT - After the War

- The Races

- The Fifty Years of Sebring

- The Seventy-Five Years of Sebring

- The One-Hundred Years of Sebring - Excerpts

- Major Thomas B. McGuire, Jr.

- Selected Excerpts

- 1949 Hendricks Field Brochure

-

Allen C. Altvater, III

- Allen C. Altvater, III

- High School Reunions

- Our Church

- HCSO - Sheriff Chaplaincy

- Sebring's Centennial Celebration

- World Changers

- Historical Society

- Sebring Air Terminal

- About the Author

- Foreword

- Chapter 1 - The Origin of Hendricks Field

- Chapter 2 - No Army Camp for Sebring

- Chapter 3 - Early History of Hendricks Field

- Chapter 4 - Hendricks Field 1941-1945

- Chapter 5 - Hendricks Field

- Chapter 6 - Hendricks Field After the War

- Chapter 7 - The Eighth Air Depot, Inc.

- Chapter 8 - Ghosts of WW II Planes Still Roar

- Chapter 9 - Congressman J. Hardin Peterson

- Chapter 10 - Historical Documents, Letters, Telegrams, etc.

- Chapter 11 - The Race

- Chapter 12 - The Races

- Chapter 13 - Reports and Memorandums

- Chapter 14 - 12 Hour Grand Prix

- Maps

- Additional Documents

Chapter 7 - The Eighth Air Depot, Inc.

The Eighth Air Depot, Inc.

Almost all Florida communities have an obsession for attracting new residents and they feel that the best method to accomplish this end is to lure “new industry.” The success of a chamber of commerce or other business organization is gauged by the ability to bring new industry to town. Following World War II, emphasis on the need of employment of service men returning from the war, was the theme of all organizations in Florida.

At the same time, most of the returning men had a desire to set up a new life pattern by establishing a business of their own. Some of these succeeded but most failed. So there was no great fanfare when two young men approached the Sebring Chamber of Commerce and announced that they were forming a new company which would be known as the Eighth Air Depot, Inc., and would engage in the business of overhauling airplane engines.

At that time, there were probably not more than four or five planes in the Sebring area and all of these were single engine, light planes, so the possibilities of a successful operation of this nature were so remote that little or no importance was viewed of the visit of these two young men.

However, this interview was the forerunner of the most important manufacturing activity in the community, exceeded only by agriculture and tourism in employment. In the more than twenty five years since the end of World War II, it has not only given employment to hundreds of citizens of Sebring, but has made possible the establishment of the Sebring Air Terminal as an industrial center and has attracted other industries to the area.

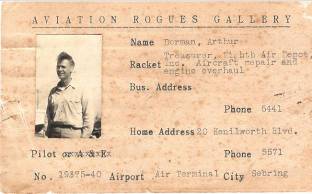

“Eighth Air” or “Eighth”, as the firm later became locally known, had its beginning, not in Sebring, but in Accra, Africa, during World War II, several years before the Sebring interview. Captain Arthur N. Dorman, who was attached to the 12th Air Transport Command, was assigned to duty at Accra which was the headquarters of the 8th Air Depot Group of the Air Technical Service Command.

The Eighth Air Depot Group repaired and overhauled planes for the American and British forces operating primarily in the Burma theatre at first but later in support of the North Africa campaign and Art was appointed to the duties of chief pilot for the tremendous operations at Accra. Before he arrived, the allies were losing many planes on the long runs to Burma, Cairo, Iraq and Iran, due to engine and airframe failures. The conditions were so critical that in the first three days of his duties, Art grounded more than thirty planes. This action brought violent reaction from a higher command who cried that “we are at war and need those planes in the air -

It also brought in an officer of high rank to make an investigation. Capt. Dorman persuaded him to pick any one of the grounded airplanes and go for a test run around the airport but they were scarcely airborne before the ship began to shake and shudder to such a degree that the investigating officer begged to be taken down. He was thoroughly convinced that there was ample justification for the grounding of the aircraft and for the recommendation that changes be made in the operation due to the vast overhaul issue.

His first action upon landing was to send a telegram to Washington. A few days later, a plane brought in Lt. George Dumont who took over command of the engine overhaul operations and so thorough was his supervision that, after that time, only one plane was lost due to engine failure although flight schedule at this base called for around-

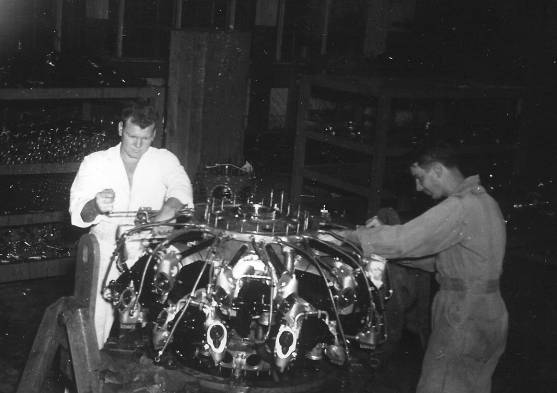

George’s background had prepared him well for this command. He had been in the Office of Education for three years and with Pratt and Whitney for five years. This firm manufactured most of the engines that powered American planes in World War II and George really knew his engines. In addition, he has always been an excellent judge of men and has demanded perfection from them, in their work.

Capt. Dorman and Capt. Dumont were bunk-

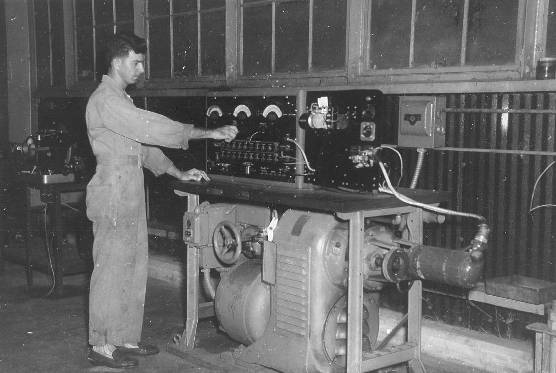

Bob and George became fast friends and, in the periods of relaxation, they speculated on what they would do when the war ended. Thus, the idea of an airplane repair facility was formed. Many of the service personnel working under Capt. Dumont’s command also were faced with the problem of planning their futures at the end of the war and, as George was in a position to observe their qualifications, he discussed the proposed repair facility with the men who had the greatest talent so that when the firm was eventually formed, these men were the nucleus of the organization. They were experts in their respective fields: Al Knight in carburetors and ignition; Roy Cameron in engine buildup; Tom Flannery in airframe and installation; and Frank Holbus as an all-

The war ended but the dream of a repair facility did not. The three dreamers were separated: George Dumont was transferred to Florida; Bob Kiel to Domestic Air Transport; and Art Dorman to a tour of duty as a base commander in the Pacific theatre. But they got together again in Miami and started a search for a location where they might make their dream a reality. Military bases were being closed all over the United States and with their vacant buildings, appeared to be the sites with the best potentials and facilities so they investigated several prospective locations including Melbourne, Palm Beach, and other Florida locations.

The ultimate choice of Sebring was just the beginning of the problems and decisions with which the new firm was beset for the next couple of years. They must have personnel and tools with which to operate and, most of all, they must have a government certificate as a CAA approved repair station before they could engage in the work on the type of planes that would ensure the success of their venture. This certificate could not be obtained until their shop was established, equipped and staffed.

The quest for equipment led to Washington and the War Assets Administration where their reputations, earned in the war, were of distinct advantage. In their shopping, they learned that the War Assets Administration was looking for agents who would help dispose of huge quantities of materials which were surplus to the needs of the government. The cash reserves were fast disappearing what with the rents they must pay to hold the buildings; the cost of equipment they were getting together and the salaries of the men they were employing to get the shop into operation, all this with practically no income while waiting for a certificate.

So the men signed an agreement with the government to act as an agent for disposing of war surplus materials and, for this purpose, they hired a selling organization known as Miami Aircraft Supply, Inc. This new venture provided income with which to carry on but, it also required a great deal of time and attention at just the time when “the Eighth” was beginning to be a reality so, when the great day came in the form of a certificated repair facility, they disposed of their agency contract and set about building one of the finest aircraft repair shops in the United States.

Bob Kiel did not live to enjoy the success of the Eighth as he and Tom Flannery were victims of a plane crash in November 1949, but George and Art set high standards which brought in business from all parts of the world and earned for them a very valuable reputation in their field.

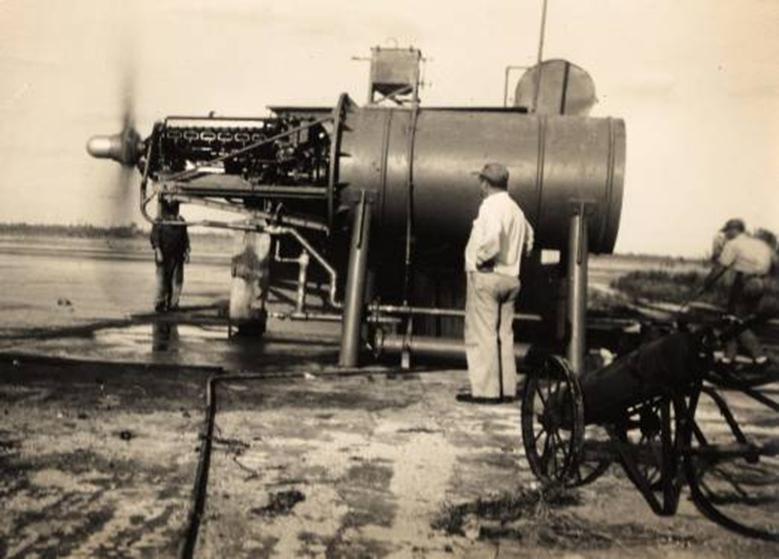

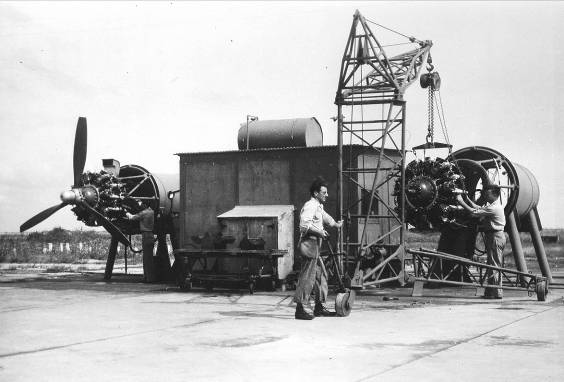

Soon after they were awarded their certificate, they accepted a government contract to recondition a large number of training-

In the first twenty years, it was determined that several subsidiary corporations would be advantageous, so Moon Industries, Montman Products, the Sebring Corporation, and Sentinel Ignition Corporation were formed to handle phases of operations outside the scope of Eighth Air. Over the years, the firms have provided steady year-

After twenty years, the volume of business had increased to the point where a decision had to be made whether the firm would “go public” or would be sold. Financial experts were consulted and it was stipulated that they would sell only if the operation remained in Sebring. In June 1969 they accepted an offer by Support Systems, Inc., and the firm was sold with the original owners contracting to manage the business for three years. At the end of this contract, George Dumont and Art Dorman retired. Their wartime dream had been successfully realized.

The full value of this company and its impact on the economy of Sebring has never been recognized or acknowledged. For months prior to their coming to the area, the Sebring City Council had been toying with the thought of definitely refusing to accept the airport after it was decommissioned. And, for months, the Eighth’s money was the only income the field produced. When Eighth Air and Miami Supply moved in the 32 million dollars worth of surplus property, seventeen warehouses began to pay rent, making the base self-

The Eighth, through its office and connections in Miami, has brought other firms to the airport thus fulfilling the predictions made during the early and hazy days that, if the City could keep the facility open and in operating condition, sooner or later it would be discovered and in demand and become a valuable industrial area. The Eighth provided the money to do just that during the critical periods.

Many other companies have come to Sebring. Some have prospered and stayed on; some have sold out and left town; and some have failed but the Eighth Air Depot, Inc., has prospered and stayed and the principals have put down their roots in the community and they continue to be most valuable citizens.

From left: George W. Dumont, Ernest R. Cash, Slayton Matthews, Nelson Golden, James P. Beard, John L. Youngblood, Homer D. Sapp, Roy D. Cameron, Thomas L. Flannery, Albert A. Knight, Oral H. Keeter, and Frank Holbus. (Photo date: late 1940’s or early 1950’s?)

Eighth Air Depot, Inc. Hangar No. 60

Robert Kiel and George Dumont, 1946

AT6 Trainers were reconditioned by EAD.

Emil Ryals and Art Dorman